This Thursday voters in Northern Ireland will go to the polls for the latest Assembly elections. Then, around 2-3 days later we will know the full results, and soon after that – if the polls are right – there could well be the waving of the first “O’Neill Must Go” protest banners for 53 years.

Of course, “If the polls are right” is something of a crucial caveat, given how they have, at times, proved to be erroneous. Nonetheless, the possibility that they are right means that Sinn Fein stand to become the biggest party in Stormont, and hence Michelle O’Neill stands to become not just the first member of her party to become First Minister, but also Northern Ireland’s first nationalist head of government, and also the second person with that surname to become head of government.

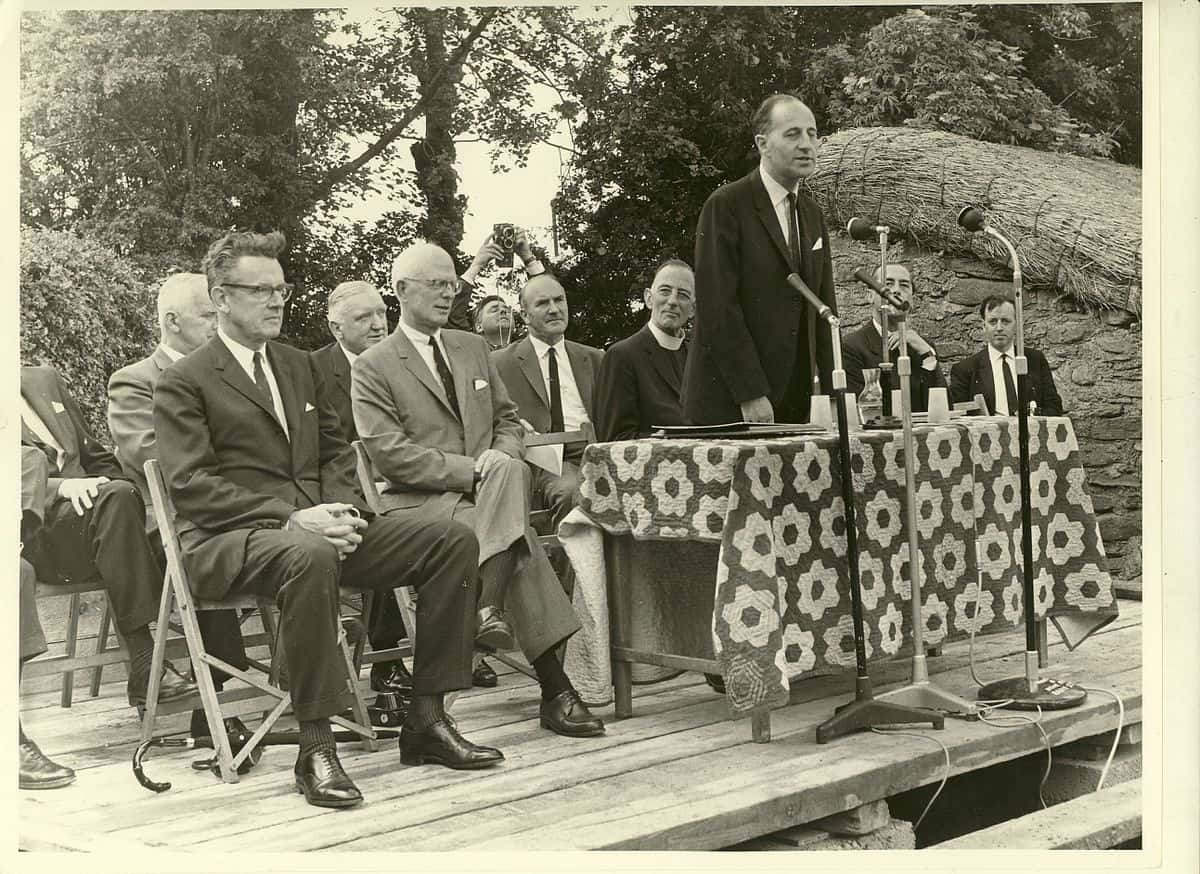

As the ancien regime‘s fourth Prime Minister, Terence O’Neill occupies a particular focus of historical interest in Northern Ireland, sandwiched as his term in office is between the IRA’s Border Campaign (or Operation Harvest) and the beginning of the Troubles. His career in Stormont is typically filed under “What Might Have Been”, given his apparently sincere but vain efforts to transform a system riven with religious discrimination, gerrymandering, sectarianism, an undemocratic political system, and economic decline. The country was changing, the world was watching, and reform was required, and he knew it. Northern Ireland needed to attract fresh investment, since unemployment was rising as the traditional industries of shipbuilding and linen were on the slide, and to prove itself attractive to investors the country would need fundamentally to change the way things were done there. As we know all too well, though, O’Neill couldn’t take the rest of his Party (the UUP) with him, and the best hopes of reforming the country in a way that would satisfy all, whatever their politics, followed him out of office in April 1969.

What tends to be forgotten about Terence O’Neill, though, is that even if he did have sensible ideas about his country’s future, he was, to put it generously, a curious candidate to sell them. Many in his Party had problems with his tactics as much as with his ideas.

The fourth PM’s entire demeanour was something of a turn-off: O’Neill was arguably quite an anachronistic and ridiculous figure. It was the 1960s: the Civil Rights movement was reaching the apex of its influence, youth movements were taking off in France, Czechoslovakia and elsewhere, and politicians in the western democracies were becoming more professional, businesslike, and media-savvy than before. Northern Ireland’s head of government, meanwhile, was an aloof and eccentric aristocrat who not only looked like Peter Sellers but also even sounded like a Peter Sellers character. The first time I saw his immortal televised “Ulster at the Crossroads” speech, I wondered if it was part of a Goon Show routine. (OK, maybe it’s just me…)

Moreover, despite his recognition that a system that looks after the interests of only two-thirds of your country’s population is ultimately not a viable system, O’Neill himself wasn’t exactly completely averse to the kind of bigotry from which he was otherwise endeavouring to move his party away. In a May 1969 interview he gave to the Belfast Telegraph shortly after leaving office, he let some pretty toe-curling ignorance rip:

It is frightfully hard to explain to Protestants that if you give Roman Catholics a good job and a good house, they will live like Protestants because they will see neighbours with cars and television sets; they will refuse to have eighteen children. But if a Roman Catholic is jobless, and lives in the most ghastly hovel, he will rear eighteen children on National Assistance. If you treat Roman Catholics with due consider and kindness, they will live like Protestants in spite of the authoritative nature of their Church.

I haven’t yet managed to get hold of the entire Telegraph interview, but I can’t help wondering what else O’Neill said, and whether his observations veered off into the Derry Girls‘ “Friends Across the Barricade” episode territory…

O’Neill’s tactics left a lot to be desired, too. Historic though the Republic’s Taoiseach Sean Lemass’s 14 January 1965 trip to Belfast certainly was, it was, to say the least, bizarre how the Prime Minister shared details of the planned visit only with a few members of his party. The meeting would be followed by others between the two, as well as between O’Neill and Jack Lynch (Lemass’s successor). The pattern would be repeated again as his term played out. Even those of us who aren’t schooled in the arts of politics know that networking and schmoozing your party tend to be more effective ways of getting things done than just announcing fundamental changes and blithely expecting your team to go along with them just because you say so. Essentially O’Neill was repeating the same errors of party leadership as those of ex-British prime ministers Sir Robert Peel and W E Gladstone, who ended up torpedo-ing their careers over the respective issues of the Corn Laws and the first Irish Home Rule bills, at least party because of that blinkered leadership style.

I’m reminded here of the words of Unionist commentator Alex Kane, who, in a Belfast Telegraph column seven years ago about the first O’Neill-Lemass Belfast summit, wrote of how Unionists are not opposed to all change point blank; what they take exception to is change being foisted upon them without so much as a modicum of consultation:

If increasing numbers of nationalists were happy enough to live in Northern Ireland then what was there to fear from cross-border co-operation on tourism and economic issues and from a strong, friendly relationship between both governments? Absolutely nothing. And O’Neill should have said as much and sold his “vision” openly and confidently.

He didn’t. Only a very small number – including some who weren’t even in the cabinet or the party – were made privy to his strategy.

Worse still, most of them weren’t actually key figures or opinion formers within the media or unionism. Had they been, they would have advised him that unionists don’t like secrecy. They don’t like finding out at the last minute. They don’t like the fact that negotiations have been conducted behind their backs. They don’t like being presented with a fait accompli.

It also at least partly explains why there was so much opposition among Unionist circles to the Anglo-Irish Agreement of November 1985 – a landmark measure with which even the future Irish president Mary Robinson (then an independent Senator for Dublin University) had problems, as she considered it ‘unacceptable to all sections of Unionist opinion.’

Ultimately, of course, events on the ground would overtake O’Neill and his government, and the over-the-top RUC response to the banned Duke Street demo of 5 October 1968 would be followed by further demonstrations and riots. Seven weeks later, in what with hindsight might be seen as the ancien regime‘s Last Chance to take control of the situation, the PM announced a Five-Point reform programme in response, under whose terms housing would be allocated on a points basis, plural voting for businessmen would be scrapped, a Development Commission would replace the discredited Londonderry Corporation, the Special Powers Act would be amended, and an independent Ombudsman would be set up to investigate complaints of discrimination. The demonstrations nonetheless continued, and a 30 November Civil Rights march in Armagh was stopped by both the RUC and loyalist counter-demonstrators led by the Rev Ian Paisley (who would later be jailed for his conduct on the day). Then, on 9 December O’Neill went on television, attempting to draw out his inner Churchill or Kennedy – although even there he fell somewhat short of their powers, as he couldn’t quite help lecturing the Civil Rights movement about his programme:

Perhaps you are not entirely satisfied; but this is a democracy, and I ask you now with all sincerity to call your people off the streets, and allow an atmosphere favourable to change to develop. You are Ulstermen yourselves. You know we are all of us stubborn people, who will not be pushed too far. I believe that most of you want change, not revolution. Your voice has been heard, and clearly heard. Your duty now is to play your part in taking the heat out of the situation before blood is shed.

But I have a word too for all those others who see in change a threat to our position in the United Kingdom. I say to them, Unionism armed with justice will be a stronger cause than Unionism armed merely with strength. The bully-boy tactics we saw in Armagh are no answer to these grave problems: but they incur for us the contempt of Britain and the world, and such contempt is the greatest threat to Ulster. Let the government govern and the police take care of law and order…

What kind of Ulster do you want? A happy and respected Province, in good standing with the rest of the United Kingdom? Or a place continually torn apart by riots and demonstrations, and regarded by the rest of Britain as a political outcast? As always in a democracy, the choice is yours. I will accept whatever your verdict may be. If it is your decision that we should live up to the words “Ulster is British”, which is part of our creed, then my services will be at your disposal to do what I can. But if you should want a separate, inward-looking, selfish and divided Ulster then you must seek for others to lead you along that road, for I cannot and will not do it.

Three weeks after this speech, which nonetheless earned him the support of most of his party and several thousand letters of support and praise, came the Burntollet clash. That would be followed by further unrest, a general election in which O’Neill lost his Stormont majority, and a number of bomb attacks by the UVF, which were erroneously blamed on the IRA (as was the idea), until finally, in late April 1969 O’Neill bowed to the inevitable and quit the premiership.

Under such circumstances, maybe the real question to ask, given all O’Neill’s shortcomings, is not Why did his strategy fail? but rather How did he manage to persuade his party to accept even the Five Point programme? Perhaps O’Neill knew, deep down, that in pursuing his big objective for Northern Ireland he was on a hiding to nothing, and that his impulsive gestures, his aristocratic posturing and booming oratory were designed only to shore up his own reputation and posterity among those who read about the history of Northern Ireland, look at his premiership and utter smugly ‘Yep, he told you so.’ If, in the final analysis, too many Unionists thought that he was going too far in his reforms and too many nationalists thought he wasn’t going far enough, then what else could have been the point of why he did what he did?

Just how distantly Michelle O’Neill is related through marriage to the fourth PM, I don’t know. Ultimately, of course, her and her party’s long-term aim is the eventual abolition of the state that Terence O’Neill tried unsuccessfully to reform. Whether she succeeds in that aim, even if she does make the top job after this week, it’s obviously too soon to say. At the very least she will be hoping when she makes televised speeches that nobody expects her to finish them with the words ‘He’s fallen in the water…‘

Based in Birmingham, Dan is a writer and actor

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.