A Great Power has been humbled, and its leader’s reputation has suffered. It has had to retreat in the face of successful military manoeuvres from a much less powerful state, and it has come in for a lot of criticism from its allies about its actions. This Great Power is discovering, in quite stark fashion, that it cannot just expect to send its soldiers anywhere in the world, lay down the law, and expect things to go swimmingly just because it wants them to.

If this scenario sounds familiar, it’s because it should do. It describes not just Joe Biden’s America on the day the last US troops are scheduled to leave Afghanistan after an operation lasting nearly 20 years, but also the US in 1975, as the North Vietnamese army and South Vietnamese NLF (a.k.a. the Viet Cong) closed in on Saigon while American helicopters lifted off. It’s also exactly what happened to the UK under Anthony Eden over Suez in 1956-7 and under David Lloyd George over Chanak in October 1922. As the old joke goes, Why does History Keep Repeating Itself? Because not enough of us pay attention the first time around…

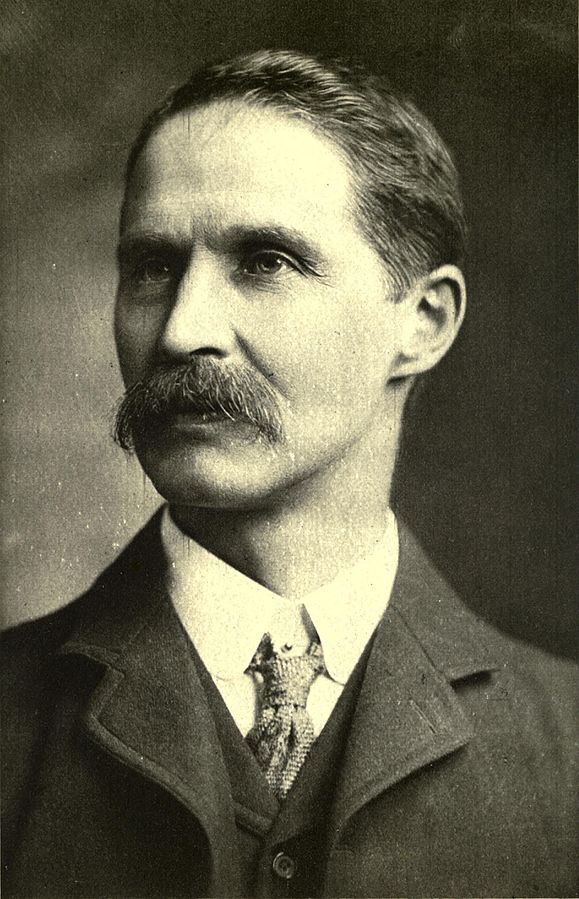

The lesson should really have been learned during Chanak – and a certain son of a Coleraine preacher was one of the first to explain the fundamental problem. In a letter to The Times on 7 October, less than two weeks before he replaced Lloyd George as Prime Minister, Andrew Bonar Law put it bluntly:

We cannot alone act as the policeman of the world. The financial and social condition of this country makes that impossible.

But what was true of Britain nearly a hundred years ago is equally true not just of the US but of any significantly powerful state in an increasingly interdependent world. If policing the world was a colossal challenge during the fallout of the Great War, it’s a nigh-on impossibility in today’s international arena. Yet, there are some out there who quite like the idea of one or more Great Powers acting as a world policeman – or “Globo Cop”, to cite a term coined by one of my former lecturers at Aberystwyth University in the late 1990s, Professor Michael Cox (now Emeritus Professor International Relations at the LSE). Anyone with even a passing interest in international current affairs knows that it’s quite a lawless world out there.

Of course, it’s not too difficult to fathom out the two fundamental reasons why the idea of a “Globo Cop” is always going to be a flawed one…

First, there are some countries out there which will be – how can this be best put? – impossible to police. These countries are what I like to call the BETGAWA nations (Big Enough To Get Away With Anything), and this is a reference not just to Russia or China, but also to countries with increasingly strong economies and more assertive foreign policies, such as India, Brazil, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and so on. The classic exchange between Prime Minister Jim Hacker and his Cabinet Secretary Sir Humphrey Appleby in Yes, Prime Minister underlines the message:

HACKER: We should always fight for the Weak against the Strong.

APPLEBY: Well, then, why don’t we send troops to Afghanistan to fight the Russians?

HACKER: The Russians are too strong!

Second, when any Great Power or aspiring one gets involved in what might be generously termed an international Policing Operation, it usually has very little to do with upholding international law and quite a lot to do with protecting their own particular interests. This surely was the lesson of Operation Desert Storm in February 1991: yes, the United States and its Coalition fought valiantly to kick Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait – but if Kuwait had not been such an oil-rich emirate would such an operation have been put together, and so successfully? At the same time that Iraq was occupying Kuwait, Indonesia was continuing to occupy East Timor, Syria was occupying Lebanon, and Morocco was occupying the Western Sahara (and is still there) – yet there was no suggestion of a similar coalition being put together to expel them from those territories. Even when a “humanitarian intervention” (and there’s a loaded term in itself) takes place, and a brutal tyrant is overthrown with the aid of a foreign invasion, this is only because the invader has reasonable ground to claim self-defence. For instance, when Tanzania under Julius Nyerere invaded Uganda in 1979, bringing down Idi Amin, that was to repel a very real invasion of Tanzanian territory that Amin had ordered. Similarly, when the Indian army stopped West Pakistan’s massacres in East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh) in 1971, that was in response to a wave of refugees fleeing to India to escape the killings.

As Bonar Law warned us before he entered Downing Street, no one single country is going to want the mantle of Globo Cop any time soon, no matter how harmonious the international order may be. This is the lesson that America has been trying to learn, on and off, since Vietnam. At least most countries of the world do subscribe to the idea of International Law, though – and if there ever is another unprovoked invasion of a small country by a larger one, there will almost certainly be some show of collective security in the form of a group of other states banding together to exert some kind of pressure to reverse the aggression. How effective the collective security and pressure in question will be depends on the countries involved, of course – as long as the aggressor state isn’t a BETGAWA power, naturally. Essentially the United Nations is little different to the League of Nations of 1920-46: both organizations are only as strong and successful as (a) their member states want them to be, and (b) the BETGAWA powers will allow them to be…

Based in Birmingham, Dan is a writer and actor

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.