While the phrase popularized by Seamus Heaney ‘whatever you say, say nothing’ endures as a code for Northern Irish character toughened by the Troubles, Colin Broderick’s  telling of his childhood reveals the language unspoken. He gives us a glimpse at those in the IRA who were never by necessity singled out by their supporters, but who carried themselves with an air of entitlement, entrusted as they were by the Catholic community with their protection and their idealism in a time when those with whom they shared a village’s main road or shops or those in a market town kept a distance, Protestant petrol stations and pubs for some, Catholic ones for others, and outside of a terse greeting, no acknowledgment or admission that could betray confidences to the occupying enemy and the long-settled watchful neighbor both.

telling of his childhood reveals the language unspoken. He gives us a glimpse at those in the IRA who were never by necessity singled out by their supporters, but who carried themselves with an air of entitlement, entrusted as they were by the Catholic community with their protection and their idealism in a time when those with whom they shared a village’s main road or shops or those in a market town kept a distance, Protestant petrol stations and pubs for some, Catholic ones for others, and outside of a terse greeting, no acknowledgment or admission that could betray confidences to the occupying enemy and the long-settled watchful neighbor both.

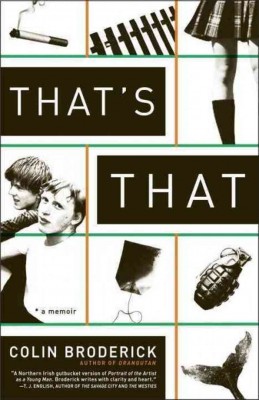

Broderick, born in 1968, raised when virginity still was expected and when the Church still dominated, tells in many instances a familiar tale. He details cutting turf and picking potatoes memorably; he comes of age into sex and brawling the way many have in his rural circumstances in County Tyrone; he emigrates only to return to the hard choices that push him off the island for good.

While some of this for all his cautious balance of intimacy and tact moves his story along as expected in respectable but not astonishing form, he intersperses the device of having his family react to the BBC news reports of atrocities to convey the span of time and the intransigence of the war in his native land. This efficiently tells the reader when the chapters are occurring in a roundabout manner, freeing the narrative from chronology. However, a spirited first ten pages of Irish history in revisionist fashion surprises–Patrick comes full of ‘retribution’ for the humiliation endured as a slave, and overthrows the comparatively preferable Celtic way of life for what soon is suffered as ‘a good dose of Christian shame, humiliation, and fear’. (3) The collusion of the papacy with the English Crown weakens the native resistance long before the Reformation forces the natives to remain loyal to Catholicism as a badge of defiance against those who plunder, inflict, and subdue. Their own form of terror, by Broderick’s infancy, sparks a violent and determined reaction from his fellow friends and cousins.

The tension grows as the war surrounds him, and while he never overplays this, or pumps up his own attitude, he demonstrates convincingly his resentment of the British and the local people–often part-time paramilitaries–who collude to control the IRA in its burrowed-in, subversive rural heartland. He lets us witness how year by year, those who become victims in the attacks and reprisals circle closer to his hamlet. Finally, in Loughgall an ambush (or SAS set-up) kills among the eight IRA operatives the two youngest, whom he knew well. This will lead him to make a deeply moral choice.

Earlier, after a harrowing incident not unfamiliar to any farm lad, he reflects on the costs of death. ‘We lose our childhoods by degrees. Inch by inch, time and circumstance steal the last of our innocence. Some of it will fall away unnoticed; some will be ripped forcefully from our fingers, other morsels of it we will bury in shallow graves, until only the shadow of youth exists, drifting in our wake like an abandoned ghost.’ (114-115)

‘Perhaps that was the real mark of maturity, I thought, finally deciding which mask suits you best, and wearing it.’ (165) The beat between ‘best’ and the final phrase shows Broderick’s timing and pacing. He prefers to reflect, pause, and continue, sifting his memories to study and analyze them after he narrates a passage from his past.

‘You just acted and spoke accordingly, never betraying an iota of your interior dialogue, even in a whisper to your closest friend, and then you had nothing at all to worry about.’ (348) His sangfroid after a harrowing examination by British army at a border checkpoint, in the company of an IRA higher-up who takes into his own wary confidence the trusted local youth Broderick, remains his studied pose. After a well-described chapter detailing his selling hash, working as an apprentice electrician on construction sites in London, and squatting there along with the ‘Tyrone clan’, one prepares for his prequel-as-sequel, Orangutan, which details his stint indulging himself and working the similar trade in Manhattan, after he emigrates.

The reason he does ends his follow-up memoir, which he had to tell. ‘I was living in a society that demanded my silence, but I needed to talk this childhood through. I needed to scream it at the top of my lungs if I was ever going to get to the bottom of this noise. And if I survived long enough to get to the bottom of it all, to understand myself more clearly, perhaps I would not have to raise my voice at all.’ At nineteen, already drinking, already made the hard man by necessity in Tyrone among his McClean clan and on the sites and in the pubs of North London, Broderick leaves for America. I will certainly seek out the second half of his life, previously published, and I welcome this writer’s voice.

California-born. Irish parentage. Teaches humanities. Reviews widely. Reads often.

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.