Doing our part: Dealing with bonfires

by Allan LEONARD

9 May 2019

Greater Shankill Alternatives, which is part of a co-ordinating initiative on restorative justice across Northern Ireland, hosted a workshop session that explored various aspects of the tradition of bonfires and the organisation’s approaches of engagement with groups who construct these structures for annual celebrations. The event was supported by Belfast City Council and its DiverseCity good relations programme.

Billy Drummond (Manager, Greater Shankill Alternatives) began by describing his organisation’s work, particularly with providing alternative pathways for young offenders. This is done by “humanising the person”, investing time to understand their motivations in order to encourage them to take responsibility for their choices.

He spoke of the significance of bonfires, especially for young loyalists. This was dramaticised with the playing of a song to the audience, in which the lyrics included, “I remember collecting the wood for the bonfire…” Drummond explained bonfires as a longstanding tradition: “Bonfires are deeply embedded in the psyche of the community. They are a rite of passage.”

The global tradition of bonfires can be traced back to ancient times, for the burning of bones and animal carcasses, and more contemporary celebration of rituals. Locally, the 11th Night (11th July) bonfires are believed to symbolise the fires lit to welcome the arrival of William of Orange’s ship at Carrickfergus in 1690. Bonfires have evolved from small street fires to massive structures we see nowadays.

Drummond described bonfires as a free form of entertainment, akin to parades on the 12th of July — a communal event that draws in the community to participate and/or spectate: “Bonfires can be the only thing that some folk can look forward to, in the absence of other activities.”

Among a list of what young people get out of participating in the creation of bonfires is: teamwork, comradeship, practical building skills, problem solving, achievement, status among peers, and connection with the local community.

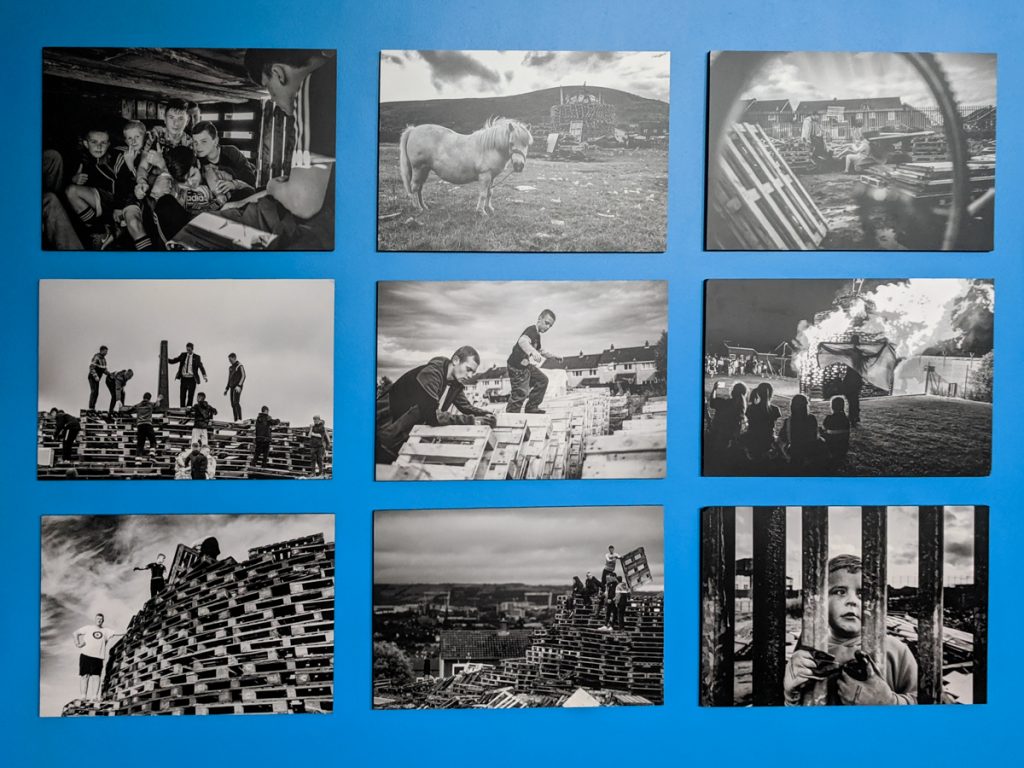

Drummond also highlighted the aim of countering the negative portrayals of bonfire culture. He cited the work of photographer, Mariusz Smiejek, whose work was on display on the back wall of the room as well as outdoors nearby on Shankill Road. Drummond noted Smiejek’s outsider’s perspective, as a recent arrival from Poland, and the significant time spent with bonfire participants: “He looks at this for what it is, without a bias that any of us would put into it.”

Drummond has strong words about the role that media can have in perpetuating negativity and conflict. He cited the case of the Irish News publishing an article about a 15-year-old who had been destroyed on social media. Ironically, there was an accompanying article on the issue of mental health: “This needs to be explored!”

For its part, Alternatives consulted with young people and creatively reinterpreted the refrain, “Good for nothing”, to a positive affirmation of “Doing good for nothing” — acts of goodwill for the sake of it. Drummond gave examples from a couple of bonfire sites: fundraising for respite care and providing a BBQ and car washes. He expressed a goal of extending the #GoodForNothing project.

Controversially, Alternatives did not engage with a bonfire scheme from Belfast City Council. Drummond explained that they did not want others to see themselves motivated by financial incentives, wishing to retain their autonomy and ability to engage with all groups organising bonfires. He also sees the bonfire scheme as becoming overly politicised.

Alternatives solicited feedback from bonfire participants. Admittedly non-scientific, Drummond provided a summary of results from their sample of 300 respondents:

- 90% believe bonfires are important and bring the community together

- 45% want to not burn tyres

- 34% have been injured building bonfires

- 24% have had an argument with a local resident

- 86% want to work with the community for safer bonfires

- 13% support beacon-style bonfires

One reason for the low level of support for beacon-style bonfires is that there is little involvement in their creations. Drummond said that while appropriate in certain, smaller venues, they remove so many of the motivations for engagement with young bonfire builders.

On the other hand, when asked about the trend of ever-bigger bonfires, Drummond answered that this can be partly explained by peer competitiveness and the interest of media outlets. Yet he defended Alternative’s perspective of “Engagement not Enforcement Gets Better Results”. He gave an example of the placement of the Irish tricolour flag on bonfires. Drummond does not approve of this, but argued that if you tell young bonfire builders not to do this, they can likely be goaded by other peers to do exactly this. He also said that he had little time for those who “are more articulate about not burning tyres versus those who burned people”.

The ensuing conversation revealed an interplay of a variety of issues that Drummond freely addressed, between safety, identity, and “not being scapegoated”. He didn’t appreciate those who come to him and say, “You have to do something about this.” Rather, he appealed for those who want to resolve issues, to come and help: “You can’t send out a policy directive and expect everyone to automatically follow it!”

Going back to his explanation of Alternative’s work, Drummond mooted, “Am I making the situation better or worse?” He said that attempting to ban bonfires altogether would be futile, although building more housing would practically reduce the number of available sites.

Drummond concluded with a remark that encapsulated the whole discussion: “Bonfires are more complicated than portrayed and we are trying to do our part.”

PHOTOS

Originally published at Mr Ulster.

Peacebuilding a shared Northern Irish society ✌️ Editor 🔍 Writer ✏️ Photographer 📸 https://mrulster.com

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.